APRIL 3, 2009 -- How quickly things can change.

Last week, Gov. Mark Sanford’s political stock was riding high after he seemingly out-maneuvered the entire General Assembly on the issue of whether to accept $700 million in federal stimulus funds.

Last week, Gov. Mark Sanford’s political stock was riding high after he seemingly out-maneuvered the entire General Assembly on the issue of whether to accept $700 million in federal stimulus funds.

Sanford, who had for months railed against the idea of the nation getting out of its current financial struggles by deepening its indebtedness, stood fast last week and said he intended to decline that portion of the stimulus package on principal.

The state was set to receive close to $8 billion in direct funding and tax credits from the federal government over the next two years, with cash infusions increasing the state’s proposed 2009-10 budget to $6.6 billion.

State legislators had been the smug ones until last week because they had Congressman Jim Clyburn (D-S.C.) on their side.

As majority leader in the U.S. House of Representatives, Clyburn had been able to insert wording into the federal stimulus bill that should have allowed legislatures in states like South Carolina, Alaska, Texas and Louisiana to circumvent governors opposed to the stimulus package and accept the money directly.

But a legal opinion crafted two weeks ago by congressional researchers and shopped around U.S. Sen. Lindsay Graham (R-S.C.) changed all that. Graham’s report, which was not a legally binding document, said legislatures accepting the money directly would violate the precept of separation of powers guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution.

Grumbling over plates of crow, the tone of Statehouse leaders began to change as they became supplicants, sending polite letters to the governor asking him to relent. Senate Finance staffers even began work on a second budget

Sanford seemingly offered an olive branch by offering to accept the $700 million, which would flow into and stabilize the state budget and increase funding for more teachers and increased healthcare among others – but only if the legislature would agree to roughly half that amount in state budget cuts. For the next two years each.

Sanford seemingly offered an olive branch by offering to accept the $700 million, which would flow into and stabilize the state budget and increase funding for more teachers and increased healthcare among others – but only if the legislature would agree to roughly half that amount in state budget cuts. For the next two years each.

So, in essence, Sanford would accept the $700 million only if the legislature would hand over roughly $750 million in cuts. Again, Sanford’s political stock was riding high.

The worm turned

And then, as Shakespeare might say, the worm turned.

This week two more opinions were handed down, one from the Obama administration and another from state Attorney General Henry McMaster, that agreed with Graham’s report. It was all but settled. Sanford and Sanford alone would have the final decision as to whether to accept the money.

And ironically, that seemed to suit many in the General Assembly just fine.

“Before now, the governor was trying to play both sides,” said state Senate President Pro Tempore Glenn McConnell (R-Charleston) this week.

Sanford’s fight against the stimulus package, according to McConnell, had been grandstanding because the governor also believed the legislature would be able to usurp the executive branch and accept the $700 million.

“He wanted to, on one hand, protest and be seen fighting it, and then on the hand have the legislature accept the funds anyway and then point the finger at us,” said McConnell.

But the Obama and McMaster opinions seemed to put the second and third nail in that coffin, according to McConnell.

Now Sanford was the one who was isolated, and the $700 million question would be his alone to answer:

Did Sanford, who heard hundreds of protesters outside the Statehouse this week, want to be the guy who turned down an enormous chunk of money when the nation was teetering between recession and depression? When his state’s unemployment had risen to over 10 percent and showed no signs of cresting? And when it became apparent that South Carolinians would have to repay their portion of the stimulus package regardless of whether they received any benefit?

Turning up the heat

One of Sanford’s ardent enemies turned up the heat on Wednesday.

On the floor of the Senate, Sen. Hugh Leatherman (R-Florence), chair of the Finance Committee, presented a scenario of where the state’s $700 million would be dispatched to if Sanford didn’t accept it.

Some $78 million would go to California, where Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger would gladly welcome it; nearly $40 million to New York; even Puerto Rico would get more than $8 million originally slated for South Carolina. Click here for a chart of what other states would get.

Even before Leatherman took to the rostrum, Senate and House leaders and Statehouse sources had said that Sanford’s people had already began shopping a deal, albeit quietly, that would allow some of the money to flow in, but still save face.

A handwritten request for comment from the governor’s spokesperson has gone unanswered.

A handwritten request for comment from the governor’s spokesperson has gone unanswered.

As of publication time, Sanford has reportedly agreed to ask for the stimulus package, but has planned to take a “cafeteria-style” approach, and decline asking for the $700 million slice.

Faced with what appears to be an unwinnable fight, will the governor cave and ask for the money before midnight tonight? Like he did in a similar fashion in December when applied in the eleventh hour for a huge federal loan to cover the state’s Employment Security Commission’s mounting bills?

“I think the governor is going to stick by his guns,” said Sen. John Land (D-Manning), who began serving in the Statehouse in 1975. “I think his last two years in office are going to be his worst.”

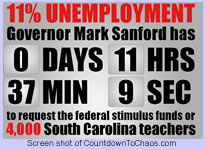

Land said his fellow Democrats in the Senate were behind the Website CountdowntoChaos.com, which features a ticking clock counting down to the deadline for Sanford to officially apply for the $700 million and the number of teachers (4,000) that could lose their jobs if the money doesn’t come through.

Land said the money would come to the state, but in time. “I believe the House and the Senate will have to craft and pass a concurrent resolution saying the governor has to take all the money. And when he doesn’t, sue him in court and force him to follow the law.”

McConnell also said the money would eventually arrive, but that he expected Congress to rewrite the stimulus bill so state legislatures can accept the money before the General Assembly would ever have to sue Sanford.

Crystal ball: Sanford may have managed to avoid an eleventh-hour capitulation, like he did when he took federal cash to shore up the state’s bankrupt unemployment commission. But he hasn’t avoided further enraging his enemies in the Statehouse and splitting the Republican caucus in the Senate, where eight to 10 senators have stayed glued to his side. Watch for a deal to be hammered out that will allow for some of the $700 million and some tax cuts/debt reduction. And, if Land was right, watch out for the next two years.